Cover Page: BreakOne and Boki in Eger, Hungary 9 Oct. 2004. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/cfs/041009_cfs_dz.jpg .

Figure 1

This independent research paper is © copyright 2006 Timothy Werwath. He wrote the paper as a senior at Wilde Lake High School, Columbia, MD, USA.

"People with money can put up signs ... if you don't have money you're marginalized...you're not allowed to express yourself or to put up words or messages that you think other people should see. Camel (cigarettes), they're up all over the country and look at the message Camel is sending...they're just trying to keep the masses paralyzed so they can go about their business with little resistance." -- Eskae

Cover Page: BreakOne and Boki in Eger, Hungary

9 Oct. 2004. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/cfs/041009_cfs_dz.jpg .

Figure 1

Wild-style graffiti. Grand Rapids Street Art. http://www.equalized.org/grgraffiti/ .

"Graffiti writing breaks the hegemonic hold of corporate/governmental style over the urban environment and the situations of daily life. As a form of aesthetic sabotage, it interrupts the pleasant, efficient uniformity of "planned" urban space and predictable urban living. For the writers, graffiti disrupts the lived experience of mass culture, the passivity of mediated consumption." - Jeff Ferrell, Crimes of Style

Graffiti is art. Aesthetic criteria and motives behind the artist's work far outweigh arguments on legality or unconventional presentation. (Stowers, Gadsby) The purpose of this research paper is to analyze and interpret graffiti's social significance as well as its intentional and unintentional goals. To understand this better, this paper also presents a history of the community that surrounds the art form and analysis of important characteristics of the culture.

Graffiti is the act of inscribing or drawing on walls for the purpose of communicating a message to the general public. The term comes from the Greek term "Graphein," which means 'to write.' Graffiti has been around since men first started drawing pictures in caves. However, the focus of this paper is not on pre-historic or amateur graffiti, but on the modern hip-hop graffiti movement that began in the late 1960's.

There are three major types of modern graffiti art. The most basic type is a 'tag,' in which the artist writes his name in his own unique style. A more advanced form of tagging is a 'throw-up,' in which the artist may use bubble-letters or 'wild style' (Fig. 1) to create a more intricate design. The next type of graffiti is a 'piece' or 'masterpiece,' which usually depicts a scene or well-known characters with some sort of slogan. This type of graffiti often requires the collaboration of multiple artists. These are most often found on subway trains (often taking up an entire car) or on private walls.

Since the root of the word "graffiti" is "to write," then graffiti can be interpreted as an instinctual human need for communication. Motives for producing graffiti vary immensely from artist to artist. However, these motives can be categorically placed in two main groups: Mass Communication/Cultural Frustration and Individual Expression.

In the first category there exist a variety of different explanations. Largely, artists in this category turn to graffiti to state their opinion on a culturally-significant situation that they feel strongly about. (Stowers) Examples of this include anti-war murals, portraits of idolized figures, or expressions of contempt for authority. (Fig. 3 and 4) Artists in this category may also turn to graffiti because of boredom, partially because they feel ostracized from society or the elite art scene. Less often graffiti crews will tag a certain area to mark territory, as to let the public know that they "own" a certain block or alley. The motives of this specific type of graffiti art come into question because of the murky border between vandalism and art, although it is important enough to be recognized.

Graffiti artists who are drawn to the art form for individual expression are much more creative with their work. They turn to graffiti because they believe that hip-hop style is the closest representation of who they are as a person and the background that they have (Gadsby Ch.3). They feel that the way they would like people to view them is best expressed through hip-hop. The basis of this is in the socialization of the person as a young child and the environment in which he or she grew up. (Giller 2) Artists in this category usually work to master intricate designs of "wild-style" graffiti that say little more than their street names, but offer very appealing aesthetics. (Fig. 5 and 6)

Without a better understanding of why artists turn to graffiti, it is not surprising that the average person's image of a graffiti artist is far from accurate. A majority of people tend to associate graffiti with vandalism. They think most graffiti artists are hoodlums or gang-bangers with nothing better to do with their time. As this paper will show, vandalism and graffiti derive from very different motives and environments. Though there is sometimes a fine line between the two, this is what gives graffiti a more organic feel.

Currently, approximately one-half of graffiti artists come from white middle- and upper-class homes, especially concentrated in suburban areas (Tucker Ch.3; Walsh 11). Though the art form was once originally relegated to low-income urban youth, the explosion of hip-hop style in the 1990's brought graffiti to an entirely new range of artistic and creative people. Kids from the suburbs seem to connect with the same message that inner-city kids are trying to communicate. They are using it to show a rejection of values and morals that are being pressured on them by their environment. (Wimsatt 11) They feel it is the only way to disrupt the sterilized, uniform isonomy of a planned suburban community and break free from its culture of materialism and consumption.

This paper covers the topic of graffiti culture in depth. It is divided into four sections that include relevant illustrations. The first part gives a history of modern hip-hop graffiti. The second part deals with the issue of graffiti's legality. The third part of the paper explains graffiti's subculture and the people involved in the art form. The fourth chapter deals with recent trends in graffiti; specifically, commercialization and its effects on the art form. Finally, the conclusion sums up the major points of the paper and infers a personal opinion on where graffiti stands right now.

Fig. 2: Kosi, Berlin, Germany.

Burn Out. 2004. Art Crimes.

http://www.graffiti.org/kosi/kosi_burn_out_freising_2004.jpg .

Fig. 3: "Infinite Justice", Sendy's, Barcelona, Spain, March 2002

Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/war/infinitejustice_afganistan1.jpg .

Fig. 4: "Grown and The War", FNA, Copenhagen, Denmark, 17 Mar. 2003.

Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/war/bushsadam_grown_thewar_fna.jpg .

Fig. 5: Themo, New Jersey, USA

Dec. 2005. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/nj/themo4200512m.jpg .

Fig. 6: Denz, North American Freight Train

2006. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.com/trains/2006trains/dzo32005.jpg .

Fig. 6: Denz, North American Freight Train

2006. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.com/trains/2006trains/dzo32005.jpg .

"Graffiti is the youth's subtle yet loud, clear and energetic response towards a society which showed no love for them, the so-called underdog" - Phase II

The origins of modern graffiti can be traced back to what is deemed the birthplace of hip-hop style, New York City. At this time, the city was almost unrecognizable compared to the booming economic hub that we know today. After the population peaked in the years after World War II, the city declined as industrialization decreased, crime rates jumped, and middle- and upper-class residents began moving out of the city and into the suburbs. (Langan 5)

What was left was a city in which many of the residents were poor and of the working class. Most were locked into laborious jobs and had little way out. This created a sense of helplessness, as they saw those who had the ability to mobilize themselves out of the filth of the city and settle in the more pleasant suburbs.

The apathy reverberated through residents of all ages. It was in this climate that the idea of defining ones self through a new identity took place. The new identity, "hip-hop," was expressed lyrically and musically in rap music, physically through break-dancing, and artistically through graffiti. This took place not only in New York City, but in Philadelphia and Boston as well. (Dennant, Ch.1)

Hip-hop graffiti started with tags. In a time before intricate wild style and other forms of graffiti had emerged, the idea was just to make a presence in the city. The first documented evidence of New York City graffiti was in the mid-1960's, when a youth who called himself "Julio 204" began to write his tag in the subway system. By 1968, his name could be found all over the city.

In that same year emerged a second name that helped to popularize the art form. "Taki 183" was a Greek youth named Demetrius who came from a working-class family in Washington Heights. In a few years his name could be found on almost every train and every subway station in the city. A New York Times reporter tracked down and interviewed Taki 183, subsequently publishing an article entitled "Taki 183 Spawns Pen-Pals." The article had an unforeseen effect when the phenomenon blew up in the months afterwards, as hundreds of writers turned to the streets to express their feelings as well. (Dennant, Ch.1; Tucker Ch.1)

The idea behind putting their names up in public and familiar places was to show a rejection of their working-class environment. Most who worked in menial, low-class jobs felt that they had no individuality in the workplace; that they were just part of the city's life-blood and could not be distinguished from the next worker. Turning to art, graffiti writers posted their names in as many places as possible, in essence to let the world know that they were still conscious and were still human beings. As Omar, a New York City graffiti writer puts it (Walsh 35):

"How many people can walk through a city and prove they were there? It's a sign I was here. My hand made this mark. I'm fucking alive!"

The explosion of this new style of art became so big that it was impossible not to notice. There were mixed reactions. By the 1980s, however, police pressure cracked down on graffiti and many well-known "writers' corners," where artists would converge to share ideas and techniques, were repainted and kept clean. The subway system began a massive clean-up program that discouraged kids from writing.

It was at this time that graffiti caught the eye of the art elite. The city was on an economic upswing, and the galleries were looking for something new and exciting to represent the re-birth of the city. Galleries in SoHo and Tribeca began displaying graffiti art from time to time. It was at this time that the graffiti art scene began to split.

Some writers saw joining the art world as an opportunity to really make graffiti a respected and legitimate art form and spread its message to a wider audience. It also made it easier to dedicate one's career to being a graffiti writer, if the art could bring in revenue for the artist.

At the same time many more artists became disgusted with the idea of putting graffiti on a white canvas. They held in contempt the idea of people gathering in a gallery to critique their work over wine and cheese. Instead, they stuck true to the roots of the art.

The reasoning behind the resistance to the gallery world goes back to the very essence of why they turned to the streets to show their art in the first place. As described earlier, most of the artists came from low-income neighborhoods. The elite of the art world paid them no attention because of their class. This brewed resentment, and when the elite finally paid them some attention they felt as if they would be "selling out" if they agreed to put their work in a gallery. They felt that they were degrading their art by turning their work into a product that art dealers could buy and sell. This following section will discuss this conflict in depth.

Fig. 7: Phresh and Jae, Steamboat, Colorado

2005. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/colorado/phresh_jae_graphics1.jpg .

Fig. 8: Ember and Rich, Portland, Maine

2006. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/maine/maine_3.jpg .

Fig. 9: "Kamikaze", SW Crew, Paris, France, October 2005. Art Crimes. http://www.graffiti.org/paris/paris_24.html .

"If art like this is a crime, let god forgive me!" - Lee, member of Fabulous Five crew

Questions pertaining to the placement and presentation of graffiti art are the most complex and controversial of all. In this area, the issue of whether graffiti is legal or illegal comes into question. The line defining the two is vague and is determined by a variety of factors. In a technical definition of graffiti under the law, many forms of graffiti are illegal. However, as with any laws regulating the expression and personal choices of people, these laws are subjective in nature.

Graffiti culture is very fragmented on this topic. Artists are pulling at opposite ends, and as a result this creates two very different graffiti subcultures. (Dennant, Ch.4) On one end are "hardcore" graffiti artists, who refuse to ever be paid for their work and strictly do throw-ups on public walls. On the other end are artists who tend to be more respectful of private property and look to the art for self-expression rather than trying to spread a message to the general public.

Artists who stick to the roots of graffiti art tend to encourage illegal graffiti. As explained in a previous section, the idea of modern graffiti art came from a rejection of authority and the ruling class, turning the worker into a "commodity" that has no personal feelings or need for self-expression. In response, artists took to public walls to express their frustration. Their argument is that the walls are part of the community, and members of the community should decide what is displayed on public walls, not outsiders.

Earlier it was suggested that laws regulating graffiti are subjective in nature. The fact is that in the eyes of a graffiti artist, a blank wall is more obtrusive and displeasing to the eye than one covered in tags. The image of a large, clean wall is a symbol of a sterilized, tightly regulated environment. (Tucker Ch.4, Farrell Q&A) The idea is that the community had no say on what would be displayed on the wall, and graffiti artists interpret this as another way to censor and discourage self-expression in the menial, low-class worker.

Arguments in favor of this type of graffiti use the principle of "eye for an eye": companies are building these huge monolithic structures, so in response one must degrade and vandalize the building. Since they cannot actually make the structure go away, they try and offer at least some sort of reaction that they otherwise would not be able to communicate because they have been disenfranchised of any means of changing the situation.

On the other end are artists that look to art galleries as an opportunity to stray away from negative connotations associated with vandals. They hope that putting their art on canvases or legally commissioned walls will give it more legitimacy and hopefully help it to gain more respect in the art world. They are not as interested in mass communicating an idea to people, but are more interested in creating art that is generally aesthetically pleasing. (Fig. 7-9)

Definitions of graffiti under the law seem to bend when money is introduced into the equation. When a community is outraged over the placement of a new commercial billboard, law enforcement officials simply state that nothing can be done about it because the corporation that placed the ad paid for it in full, so therefore it is rightfully theirs. In reality, it belongs to the community just as much as the corporation, since it is in plain view and the public must view it every day, whether it wants to or not.

Graffiti artists claim they have just as much a right to say what they want to say as do corporations. Since street advertising and large-scale billboards have become an acceptable part of the landscape, only the ones with money get to decide what goes where. It is in the best interests of corporations to only make their voice heard and for law enforcement officials to track down people who put up messages without first purchasing the rights to an area viewable by the public. Artists find this very offensive and an unfair advantage to the upper-class. One interesting subculture of graffiti art that specifically deals with this paradox is "culture-jamming."

Culture-jammers attempt to sabotage large-scale advertisements with graffiti. There are two ways in which they do this. One is by renting out a billboard by pretending to be a real company, and then putting up a piece that satirizes corporate advertising. The other is by writing over existing corporate advertisements with graffiti that changes the meaning of the ad. The first page of this report features the work of Ron English, currently one of the most famous culture-jammers around.

Fig. 10: DSK, Saudi Arabia 2005. Art Crimes.

http://www.graffiti.org/istanbul/saudi_arabia_dsk_istanbul.jpg .

Figure 11

Fig. 11: JEJ Crew, China 2005. Art Crimes.

http://www.graffiti.org/china/4skvsieforcbgt.jpg .

Figure 12

"To pour your soul onto a wall and be able to step back and see your fears, your hopes, your dreams, your weaknesses, really gives you a deeper understanding of yourself and your own mental state." - Coda

What truly motivates someone to write on a public wall, for others to see? Who is it that is doing this, and why didn't they just grab a pen and a pad and keep it to themselves? These questions have caught the interest of many sociologists, psychologists, and cultural anthropologists. To get a better understanding of how graffiti culture came to be what it is today, one first needs to step back and look over the basic elements of hip-hop culture, elements that may have been overlooked because of the diversity that it has today.

Research has shown that the identity of a person is a direct consequence of heredity and environment. From birth, a person does not choose the path they'll lead, but instead is guided in one direction or the other through socialization that has been dictated by opportunities around them. (Weiten) Someone may diverge from this and form their own unique identity, but the roots of that identity still hold true to their socialized selves. In a larger context, this can be loosely applied to an entire culture.

The people who first began the hip-hop movement were at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid. The founders of hip-hop were not born into wealth, but instead were expressing their jealousy towards those who were. In essence, graffiti is an indirect result and a modern response to the class struggle in America that has been going on for generations.

In a class system, one naturally wants to move to the top and maintain that position. A majority of people born into a free-market society are indoctrinated with capitalistic values, and to them it is seen as a positive and constructive thing to gain wealth and maintain vast amounts of capital that will extend beyond that person or society's lifetime. This is a basic survival instinct, and has been proven throughout history: the pyramids of Giza, the Roman Empire, or the practice of ascribed wealth, to name a few examples.

Unfortunately, urban lower-class youth are often completely disenfranchised from any opportunities to move up the ladder and attain wealth. Instead, they are locked into a social situation in which they work full-time to make ends meet and have very little left over. Even worse, constant struggle to just meet basic needs encourages them to spend their free time (and money) doing things that are entertaining and not necessarily constructive.

Luckily the instinct to remain alive that each person has cannot be dismantled so easily. Although older people who have been locked into these situations for a long period of time may grow apathetic and find such forms of expression meaningless, the youth have yet to be completely changed by their environment, and can still be influenced by their hereditary survival instinct. They still want to attain or create something that people will remember them by, something that will keep their message living beyond the grave. (Esposito) Taking this idea and adapting it to their urban environment and available resources explains the basic reasoning behind why they would choose to write something for the public to see. Spray paint and permanent markers were chosen especially because they were much more difficult to censor.

Devon D. Brewer, a sociologist who has studied graffiti extensively, claims that "there are four major values in hip hop graffiti: fame, artistic expression, power and rebellion." (Brewer 188) Although artistic expression can be applied to any form of art, the other three values are fairly unique to hip-hop and symbolize the envy of disenfranchised youth. Upper-class youth are often born with power and fame, since these are things that come with ascribed status. Rebellion is something that rich youth often take for granted as an alternative to their current way of life, without realizing that many people who are locked into a certain economic situation are not afforded that alternative without risking further hardship or even death. Like the story of the forbidden fruit, lower-class youths have been denied these opportunities all their lives, so they want them even more than the rich do.

These motives can be used to explain the origins of graffiti, but they do not thoroughly define graffiti today, now that it has spread beyond its original socio-economic barriers. Reiterating the opening point, culture is formed in a very similar way to the way a person's identity is formed. To this effect, a culture is constantly changing, just like a person. What allowed this change to occur was creating new and improved technology that allowed different types of people to experience hip-hop culture.

Graffiti changed because more and more people connected with the rebellious spirit of hip-hop. Middle- and upper-class youths, especially in suburbs, have lots of free time to do as they wish. Although this liberty often creates and encourages a materialistic consumer culture, at the same time the youth are afforded many more chances for educating themselves. Especially in the suburbs, this education is causing a conflict. (Ferrell 30) Suburban youth are educating themselves to the point where they reject the sterile, superficial culture of their surroundings and look for an alternative way of life with more meaning. Specifically, many turn to hip-hop and graffiti.

Fig. 12: Chuck, Managua, Nicaragua 2003. Art Crimes.

http://www.graffiti.org/nicaragua/chuck_totem_2003.jpg .

Fig. 13: H3 Hummer Advertisement by TATS Cru.

The ad was defaced within one week and removed.

2005. Irena Tejaratchi.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kittenclaw/19879959/ .

Fig. 14 & 15: McDonalds and Coca-Cola ads, TATS Cru, New York City

McDonalds Advertisement. 2005. Adam Crouch.

http://the-raw-prawn.blogspot.com/2004/09/mcdonalds-uses-graffiti-to-woo-us.html .

Coca-Cola Advertisement by TATS Cru. 2003. Lisa Whiteman.

http://www.lisawhiteman.com/hfiles/photoalbum/signs/65.html .

Technological developments in recent years have globalized modern graffiti culture. A quick glance through a graffiti magazine or gallery will show the viewer artwork from every inhabited continent of the Earth. (Fig. 10-12) Specifically, the Internet, through the use of centralized graffiti galleries and forums such as Art Crimes, has revolutionized the ways in which ideas and techniques are shared and critiqued by other artists. It has also inspired some who would have never thought to write graffiti on their own.

The prevalence of websites like Art Crimes is evidence that graffiti is a popular tool for mass communication and has an influence that can be used in a variety of different ways. Mass communication by itself is simply a force and can be used positively or negatively, much like any other force. Used in one way, graffiti can spread positive messages to inspire youth to rise up and work together as a community to change a social situation. (Fig. 3 and 4) In another way, graffiti can be used for materialistic or profitable ends that do little to convey a message or opinion to the average person on the street. (Fig. 13-15)

Originally, graffiti was more often used for communication rather than the profit. In the circumstances from which graffiti grew, social messages were often seen as important to incorporate into the artwork. Now that graffiti has been lifted out of its original context, the message is not emphasized as much. In a sense graffiti has "splintered" into a variety of subcultures that deviate from its original style.

One such subculture is street advertising. Many multinational corporations have selected graffiti writers to spray their logos and ad campaigns onto city streets in return for a paycheck. Companies that have practiced this include Coca-Cola, Nike, McDonalds, AM General Corp. (maker of the Hummer), IBM, and TIME magazine.

The use of graffiti in advertising is not an inherently bad idea. TIME magazine's advertisement (Fig. 16) paid respect to graffiti culture and did not use graffiti to push their magazine, but instead used graffiti to pose a question in the viewer's head about what graffiti is. At the bottom it provided a link to an article on TIME's website on whether graffiti is vandalism or art:

Fig. 16 - TIME Magazine ad by Cope2, New York City

Unfortunately, a conflict arises when graffiti is used for advertising consumer goods. Originally, graffiti's message to the working class was that they were not pawns of the ruling elite, and that they must use any means necessary to stand up against being exploited. As previously mentioned, the lower class was usually locked into a cycle of poverty that was difficult to break out of. The cycle was perpetuated by long working hours that brought in very little pay, which in turn encouraged workers to spend all their free money on entertainment that kept their minds off work.

From this perspective, the use of graffiti to promote a commercial product is bitterly ironic. In a sense, it is being used to encourage the stratification of society, although it was originally created to break free of those very chains that were interfering with quality of life. Graffiti is being used to encourage today's youth to spend their hard-earned money on products they don't necessarily need.

For example, picture a teenager who works five or six days a week to help provide money for himself and members of his family. His parents cannot provide him with spending money, so he works long hours so that he can buy the things he wants. Having been indoctrinated by materialistic values that are glorified in mainstream rap, he finds pleasure in buying the latest Nike or Adidas shoes. Walking down the street, he sees an ad promoting a new pair of two-hundred dollar Nike shoes, which uses dazzling graffiti art to sell the product. The ad convinces him to buy the shoes, giving him immediate gratification.

This was not the vision of the original "bombers" who took to the streets in the early 1970s to spread their message. Ingrained deep into the roots of graffiti is a loud and clear message that the lower class deserves as much respect and equality as does the upper-class. To achieve this goal, artists need to realize the things that are keeping them locked into poverty and work to correct them.

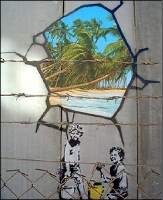

The following are photographs of the work of UK graffiti artist Bansky. He visited the Wall of Separation built between Palestine and Israel and sprayed a number of politically-motivated works. The pieces are meant to encourage people to question why it was built in the first place.

Art prankster sprays Israeli wall. 5 Aug. 2005. BBC News Online. 6 Mar. 2006 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4748063.stm .

Banksy at the West Bank barrier. 2005. Guardian Unlimited. 6 Mar. 2006 http://arts.guardian.co.uk/gallery/0,8542,1543331,00.html .

There is a line between graffiti and vandalism. The social motives and implications of graffiti have legitimized some forms of graffiti as art. Further, aesthetic qualities of the work fully validate graffiti art as an art form.

The average reaction to the sight of graffiti tags by someone who is unfamiliar with graffiti is that it is a cause of urban decay and a detriment the quality of life in the city. In reality, the opposite is occurring. A large number of graffiti tags is a response to urban decay; a cry for help from the disenfranchised masses that are struggling to survive. Though a clean city may superficially seem in better condition, this is because the working class (those who make the city work) have not yet been pushed to a point where they need to turn to the streets to express their frustration and resentment, or because graffiti has been suppressed to a point where it is no longer noticeable.

In summary, graffiti's motives stem from the dehumanization of the working class. Agitated youth took to the streets to protest the ways in which they were categorized not as people, but as a resource for production. These youths took to the streets because of a basic survival instinct, which pushed them to use any means necessary to leave a significant, lasting impression on their own culture or community.

Although it is the most significant aspect of legitimizing graffiti as an art form, the attraction for most fans of graffiti art today is no longer in the social motives. The artistic creativeness and originality of graffiti art catches the eye of potential artists that are looking for new ways to express themselves. A new generation of people has connected with graffiti because it has been developed outside of the traditional avenues for artistic expression and has been brought to them by new and improved ways for people to communicate with each other.

Take a minute to examine the work of artist Dytch66:

Fig. 17: Dytch66, Los Angeles, CA. 2006. Art Crimes.

http://www.graffiti.org/dytch66/06_mr_50mm.jpg .

The creation of a three-dimensional piece such as this challenges the artist to use his or her knowledge of complex geometry, proportions, shading, and patterning. Such a work cannot be merely written off as "vandalism" because the artist spent a large amount of time and effort working on the piece to make it look exactly as he wanted it to. Also, the work forces people who otherwise only appreciate art that was drawn traditionally and displayed in an artistic establishment to accept art that has been created outside of those limitations. (Stowers)

The techniques and form used to create these works separates graffiti from graffiti art. Anyone can create graffiti by writing something on a wall to communicate a message to the general public. In essence, graffiti is only considered graffiti art if it has something that catches the eye of the viewer. Luckily for the artist, there is no one traditional way to do graffiti art, because it was developed outside of traditional artistic environments. These eye-catchers are left up to the creativity of the artist and can be anything from the use of patterns, neon colors, typography, to the use of unconventional tools for graffiti, such as computer-created graphics.

Today, graffiti art is flourishing and will continue to flourish, whether it is accepted by art institutions or not. For graffiti to be on the same level as other traditional forms of art and receive the respect it deserves, however, two things need to occur. One is that the institutionalized art world needs to accept graffiti as a legitimate art form. Once this has occurred, the art world needs to promote a better understanding of what graffiti is and where it comes from.

This is already occurring. Since the end of the 1990s, the Brooklyn Museum of Art and other galleries in New York City have displayed numerous photographic exhibits of graffiti art from around the city. Last month, the Smithsonian Institution announced a new exhibit, "Hip-Hop Won't Stop: The Beat, The Rhymes, The Life," which features works by the graffiti elite. The exhibit is currently under construction but will become a permanent part of the American History museum.

It is only a matter of time before hip-hop graffiti artists are being compared to the great artists of the world. Rightly so: graffiti art is one of the most intricate, creative, and impressive forms of art, and it is becoming more and more popular each day.

"About Graffiti." Speerstra Gallery. 9 Oct. 2005 http://www.speerstra.net/graffiti.htm . Speerstra Galleries commissioned one of its artists to write this short history of hip-hop graffiti. Though its not well researched, it still offered some interesting topics. It offered a lot about the first graffiti art show, through the work of Hugo Martinez, a sociology major at City College in New York who first saw the potential of graffiti as an art style.

Branwyn, Gareth. "Jamming the Media." Black Hole (1992). This essay explores a correlation between cyberpunks (those who write viruses, pirate software, or do other things to disrupt commercial business on the internet) and culture jamming in graffiti (writing satirical graffiti over advertisements and billboards). Gareth links the motives behind the two and also shows the very anti-capitalist sentiments among the two groups.

Brewer, Devon D. Hip-Hop Graffiti Writers' Evaluation of Strategies to Control Illegal Graffiti. 1992. Human Organization 2. Dr. Devon Brewer has published a very interesting analysis of why people are motivated to put their artistic work in public places. The paper examines the motives and explains that most people do it as a way of becoming famous in the graffiti subculture of their city. They also do it for personal gratification, so as when they are walking the streets of their city they see their work as part of the city.

Bushnell, J. Moscow Graffiti: Language and Subculture. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1990. Bushnell examines the graffiti subculture that had become increasingly popular in the early 1990s. Bushnell follows a group of kids that call themselves the "Snake-Writers" and explores their motives and the tactics they use when creating their work. Bushnell becomes close to the kids and discovers why this art has become so popular among youth in Moscow.

Curtis, Cassidy. Graffiti Archaeology. 16 Aug. 2005. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.otherthings.com/grafarc. Graffiti Archaeology is the study of graffiti-covered walls as they change over time. The grafarc.org project is a time-lapse collage, made of photos of graffiti taken at the same location by many different photographers over a span of several years. Most of the photos are from San Francisco, over a time span from the late 1990s to the present.

Dennant, Pamela. "Urban Expression...Urban Assault...Urban Wildstyle...New York City Graffiti." Art Crimes. 1997. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/pamdennant.html . This paper explores the rich history of graffiti writing in New York City. It offers two distinctly different definitions for the terms graffiti and vandalism, and argue that the true "problems" of graffiti are perceived differently by those motivated to do it. Through this analysis, graffiti is seen as a governmental failure rather than a subculture dedicated to vandalism, thus recognizing the subculture as one devoted to establishing an art form of seriously developed talent, skill and style, and even an act of liberation.

Esposito, Rashaun. "The Artistic Construction of Counter-Culture." Art Crimes. 2005. 9 Oct. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/esposito.html . Pashaun Esposito offers an interesting alternative to the current graffiti 'problem'. He says one first needs to admit that graffiti will not go away, as it is ever expanding. The alternative to having graffiti in public places and rival graffiti 'wars' is to set up murals in communities and allow the artists to spray in designated areas. He explains that it is a problem that must be dealt with by the community.

Fadiman, A. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures. New York: Noonday Press, 1997. This is a book that was assigned for my Cultural Anthropology class. It provides an objective view of what happens when someone from a traditional culture that is not as advanced as Western culture is in need of modern medicine. It follows a Hmong woman, a tribe in Northern China, and her trip to America to have heart surgery. It examines the complications that occur from the collision of their cultures.

Farrell, Susan. "Graffiti Questions & Answers." Art Crimes. 1994. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/graffiti_questions.html. This is an FAQ on graffiti, published on a website that contains many perspectives and thorough analysis of the topic. It is basically an "Everything you ever wanted to know about graffiti but we're afraid to ask" web site. Too much information to summarize, it is broken down into what, why, and how.

Fernstrom, Katherine, Dr. Howard County Community College. Fall 2005. Mrs. Fernstrom is teaching the Introduction to Anthropology class that I am currently taking at HCC. She has given me tips on writing an ethnography, as I will be doing, and also about the anthropology field in general. Her class is an overview on how to break into the field of cultural anthropology, what is expected, and what is to be studied. This knowledge will help me with my report.

Ferrell, J. Crimes of Style: urban graffiti and the politics of criminality. New York: Garland, 1993. This is an interesting book that covers the topic of graffiti in low-income neighborhoods in various cities around the country. Ferrell catalogues a trip he takes around the country to examine different perspectives on this problem. The author interviews various graffiti artists and provides many insights into the subculture, such as what is apparent in graffiti art in relation to expressing one's talents and abilities, artistically as well as in real-life. It also examines the attitude towards graffiti by the police and other authorities in the cities.

Gadsby, Jane M. "Looking at the Writing on the Wall: A Critical Review and Taxonomy of Graffiti Texts." Art Crimes. 1995. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/critical.review.html. This is a very interesting essay that is broken down into four categories: a definition of graffiti, methodological approaches, graffiti research, and the future of graffiti. In analyzing motives for producing graffiti, she breaks it down into to main categories: Mass Communication/Reflexive Communication and Individual Communication. Mass Communication is the need to express oneself or pleasure in aesthetics, while Individual Communication deals with expressions of resentment or marking of territories.

Giller, Sarah. "Graffiti: Inscribing Transgression on the Urban Landscape." Hip-Hop Network. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.hiphop-network.com/articles/graffitiarticles/inscribingtransgression.asp . Giller discusses how graffiti is a outlet for the younger generation that feels that it has been shut out of the mainstream art world and it's establishments. As a last resort to get recognition for their work, graffiti artists take to the streets to make their work visible. Giller infers that the art world is "monocultural" and that art houses and curators make up a cultural elite that is Eurocentric.

"Graffiti." Wikipedia. 24 Sept. 2005. 25 Sept. 2005 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graffiti_art . A well-written piece written on an independent encyclopedia website, Wikipedia, which allows users to revise articles (subject to approval). The article describes graffiti, ancient and modern, the legal situation surrounding the art movement, famous graffiti writers, and the movement as it has expanded beyond the borders of our country.

Grivetti, L. Graffiti - Tagging: Ancient and Modern. University of California. 10 Sept. 2005 http://nutrition.ucdavis.edu/olympics/Sports/graf.html . This website compares and contrasts what was considered 'graffiti' in ancient times and how what is described by the same word today is very different from then. Grivetti compares the reasons people would write in public places and also the styles in which they would write. He provides many images to compare the two.

Haviland, William A, et al. Cultural Anthropology - The Human Challenge. Los Angeles: Thomson Wadsworth, 1999. This is the text book assigned for my anthropology class. It has chapters that are useful, such as how to observe a group and stay objective when writing an ethnography of that group. It also has interesting examples of ethnographies taken in the past.

"History of Graffiti." JAM2DIS.com. 9 Oct. 2005 http://www.jam2dis.com/j2dgraffitihist1.htm . This is not a very well-written piece on the subject. Seems like it was written by someone who is part of the culture, but did not properly research the topic. However, the article provides some insight into how this ancient art re-emerged as a part of the hip-hop movement and why it was significant to the growth of hip-hop to the point where it is today.

Hollands, Marie. "Graffiti is Art!" Original UK Hip-Hop. 2003. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.ukhh.com/elements/graffiti/graffiti_is_art/ . Hollands examines whether or not the introduction of graffiti into the art world is really the downfall of the movement itself. She defines graffiti as a subculture that derived from the hip-hop movement, and that its complete basis is on art that is non-commercial and for general public. She states that creating an elite and involving money in the movement could be very detrimental to it in the end.

Jacobson, Staffan. "A Brief History of Graffiti Research." Rooke Time. Sept. 2001. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.rooke.se/rooketime26.html . An interesting study of how scholars have gone about researching graffiti over the years. His timeline goes all the way back to about 1593, when "Roma Sotteranea" was written about official and non-official inscriptions in the catacombs of Rome. I used this to find many good articles on the topic.

Jacobson, Staffan. "The Spray-Painted Image: graffiti painting as type of art movement and learning process." Aerosol Art Archives. 1996. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.djingis.se/memb/ovre/aerosolart/abstract.htm . Jacobson relates graffiti to modern-day culture and provides some theories on socialization into the graffiti art world. He examines the social background and social patterns of the "writers". They are found to be in general quite ordinary, but unusually creative. It also deals with the creation, expression, content and meaning of their artwork, and it is compared with several other traditions like Scandinavian ornaments, Art Nouveau, psychedelic art and traditional calligraphy.

Jay, Pop N. "Graffiti Culture - A scholarly essay." Online posting. 28 Mar. 2005. Graffiti Board. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.bboy.org/t62351/s.html . This is an essay on graffiti culture written by someone who is actively involved in the culture. He analyzes the history, subculture, recent movements, and graffiti as a social change. He takes a closer look at "culture-jammers" who are graffiti writers who take pleasure in "parodying advertisements and hijacking billboards in order to drastically alter their messages." These culture-jammers are a radical element within graffiti culture that are trying to retain complete non-commercial involvement in the movement.

Lynch, Andrew. "Youth Control: Young People and the Politics of Hip Hop Graffiti in Aotearoa, New Zealand." Sociological Assosciation of New Zealand 13.1 (May 1998). 25 Sept. 2005 http://saanz.science.org.nz/Journal/Availabl.html. Past Issues, 1998, Vol. 13. Lynch does an interesting analysis of the youth culture in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and examines their struggle with what he calls "the demands of contemporary capitalist societies." He examines one outlet of their frustration, graffiti art, and explores the various techniques that the government and police use to both eliminate hip-hop graffiti and punish the writers.

Noah, Josephine. "Street Math in Wildstyle Graffiti Art." Art Crimes. 1997. 9 Oct. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/streetmath.html . "Wildstyle" is a form of graffiti composed of complicated interlocking letters, arrows, and embellishment. I have personally been very interested in how such artists are able to perceive proportions, size measurements, etc. while in the field. Noah does a study of what is required mathematically when writing wildstyle and the amount of mental computation it requires.

Powers, Lynn A. "Whatever Happened to the Graffiti Art Movement?" Journal of Popular Culture 29.4 (July 1999): 137-142. This book examines the decline in the number of graffiti artists since the 80's and early 90's. Graffiti thrived during the time, at the same time and the rise of the hip-hop movement in music. However, hip-hop continued to grow and is a popular genre today. However, graffiti has fallen out of style and is now considered cliched in some respects. This book analyzes why this happened.

Reed, Allen Walker. Classic American Graffiti: Lexical Evidence from Folk Epigraphy in Western North America. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Maledicta Press, 1977. This study presents graffiti collected especially from public lavatories in the summer of 1928. Reed's belief was that 'no emanation of the human spirit is too vile or too despicable to come under the record and analysis of the scientist.' The book begins with an introduction in three parts: 'The nature of obscenity,' 'Folk epigraphy,' and 'Bibliographical note.' Then follows the 'Glossary of stigmatized words,' presenting the data and analysis.

Rubin, Sara. Art Crimes. College of William and Mary. Spring 1996. http://www.wm.edu/so/jump/spring96/graffiti.html . Rubin, a student at the College of William and Mary in central Virginia, takes a look at the radical crackdown on graffiti writing in the capitol, Richmond. The article was written after two graffiti-writers were sentenced to jail-time for their work. She analyzes how graffiti is much less respected in art circles because it does not have any corporate basis or money-making opportunity. Therefore, it is looked down upon as a lower form of art.

Schjeldahl, Peter. "Graffiti Goes Legit - But the 'Show-Off Ebullience' Remains." New York Times 16 Sept. 1973: 25B. This is an article posted in the New York Times in 1973, when graffiti first originated. It is a subjective point of view, as the author is obviously aware of graffiti and is not in favor of it. He describes the movement as 'show-off' and not really a form of art. This article provides an insight into another point of view on the topic.

Shostak, M. Nisa: The Life and Words of a Kung Woman. Greenville, NC: Vintage Books, 1983. This is a book about the efforts of a woman from the Kung tribe that is trying to move into the modern world. The Kung are a group in South Africa that still follow the hunter-gatherer way of life. The book examines the cultural clash when Nisa tries to learn English and ease her way into the South African economy. An interesting ethnography.

Snover, Doug. "The writing is on the wall...and the fences and Dumpsters, too." Wrangler News. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.wranglernews.com/graffitiguy.htm . Tim O'Neil is someone who is paid to cover up graffiti. Within 24 hours of getting a call about new graffiti, O'Neil will cover up the work and replace it with something he feels is more aesthetically pleasing. This is very controversial, because what he considers to be acceptable and what graffiti-writers spend their time working on to create a work of art they find acceptable are two very different things.

Steinberg, Paul, and A.M. Oliver. "The Graffiti of the Intifada: A Brief Survey." Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (July 1990): pg. 56. Curiosity brought me to this paper that turned out to be very informative. It examines the pivotal role of graffiti in the Intifada, and the dangers that are involved with it. It analyzes different types of graffiti and interprets the use of different symbols and remarks on whether their intention was to warn, to convey political messages or to be simply commemorative.

Stewart, Susan. "Ceci Tuera Cela: Graffiti as Crime and Art." Life After Postmodernism: Essays on Value and Culture (1987). Stewart provides a unique perspective since a member of her family was once a 'bomber.' She witnessed many fights between her brother and her parents on the morality of graffiti writing and whether what he was doing broke the law. She analyzes whether or not there should be a distinction between illegal graffiti and graffiti that is generally aesthetically pleasing.

Stocker, Dutcher. "Social Analysis of Graffiti." Journal of American Folklore 85.358 (1971). This analysis by Stocker comes after the surge in the hip-hop movement of the 70s. By the late 80s, when this was written, hip-hop was almost becoming mainstream and was not considered as unique and did not have the same underground feel to it. Stocker analyzes the differences in what becoming more commercialized and mainstream did to the hip-hop community.

Stowers, George C. "Graffiti Art: An Essay Concerning The Recognition of Some Forms of Graffiti As Art." Art Crimes. Fall 1997. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/stowers.html . Stowers argues intently that graffiti art is an art form. The essay explains the reasons, including aesthetic criteria, as to why it is an art form and why this far outweighs the criticism of illegality, incoherence, and nonstandard presentation. The objective of this paper is to explain how graffiti art overcomes these concerns and thereby can be considered as an art form.

Tavernise, Sabrina. "Citing 1st Amendment, Judge Says City Must Allow Graffiti Party." New York Times 23 Aug. 2005: B1. Earlier this year, Bloomberg's administration revoked a permit for a block party based upon legalizing graffiti as an art form. The party featured painting graffiti on mock subway cars. However, the permit was reinstated after a judge ordered Bloomberg to do so. Interesting analysis of law vs opinion in trying to regulate an art movement.

Taylor, Eric. "Graffiti in Ostia, the harbour city of ancient Rome." Ostia Antica. Jan. 2004. 9 Oct. 2005 http://www.ostia-antica.org/inter/graffiti.html . This a website written by a group researching the history of the ancient Roman port, Ostia. So many people went through the port that there is an immense amount of graffiti collected from the town. The site analyzes the styles that were written, what languages were most common, and the topic of most of the graffiti. They conclude most of it had to do with business or it was obscene.

CL. "A Modern Perspective on Graffiti." Art Crime. 1995. 25 Sept. 2005 http://www.graffiti.org/faq/cl.html . CL explains the origins of graffiti, back to ancient times, and why it re-emerged with such vigor in the early 1970s. He goes into detail about the early hip-hop movement in New York City, and how complete intolerance to the movement at the time resonated and actually made the problem of graffiti worse, as kids turned more to tags, or uglier, quick-hand graffiti.

Tucker, Daniel Oliver. "Graffiti: Art And Crime." Hip-Hop Network. ca. 1999. http://www.hiphop-network.com/articles/graffitiarticles/graffitiartandcrime.asp . This is a first-hand account of the graffiti subculture in the Lower East Side of New York. Tucker was involved in writing graffiti for many years, and he reflects back on the history of the movement, reasons for doing it, his comparison of graffiti to the art elite of today, and finally he offers insight into a positive link between graffiti and the community in which it is written.

United States. Department of Justice. The Remarkable Drop in Crime in New York City. By Patrick A Langan. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004.

Walsh, Michael. Graffito. Berkley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1996. Written by sociologist Michael Walsh, this paper examines a form of graffiti called "bombing", in which basically the artist tries to write his "tag" in as many places as possible. The tags are usually not done with any quality and are abundant everywhere. Though this is looked-up as the lowest form of graffiti art, the artists try and rationalize their motives for why they do it.

Weiten, Wayne, ed. Psychology: Themes and Variations. 5th ed.

Wilder, A. "The Merits of Art: Theatre and Graffiti as Beneficial to Society." Art Crimes. 1999 (or slightly before) http://www.graffiti.org/faq/wilder.html . In summary, this article describes that the problem with graffiti, is in its very nature. Graffiti now resides mainly on the sides of buildings and subway cars, presented for all society to see. "Defacing" public property, in almost all places on this planet, is illegal. According to Wilder, "it is the vandalism aesthetic that gives graffiti its validity." Additionally, Wilder points out that graffiti is an act of defiance, and "sometimes the message of rebellion gets confused as chaos and a blatant case of delinquency, which is unfortunate."

Wimsatt, William Upski. Bomb the Suburbs: Graffiti, Freight-hopping, Race and the Search for Hip-Hop's Moral Center. Chicago: The Subway and Elevated Press, 1994. Wimsatt relates two growing trends in our society: the hip-hop movement and suburban sprawl. He relates the individualistic, isolationist tendencies of the suburban culture to that of an artist in the hip-hip world, who himself is constantly trying to express himself uniquely and show what he can do as an individual. He examines the culture in the UK as well as US.

Contact: Timothy Werwath or yo@graffiti.org about reprinting or other issues.

This document is archived at http://www.graffiti.org/faq/werwath.html