The Bombing of Babylon: Graffiti In Japan

By Natalie Stanchfield

Long Island University, Friends World Program Kyoto, Japan

An artistic movement more than thirty years strong, it has spread into an international phenomenon, boasting a thriving community of thousands of members worldwide. From prehistoric cave art to its modern day counterpart, the form of expression at the root of this artistic movement is a part of universal human culture. It is present in all stages of history, part of every civilization, mentioned in ancient texts like the Bible, and widely practiced today. The art form experienced an incredible boom in popularity in the late 20th century and developed a distinctive new style in the 1970's. The design aesthetic it introduced has become well recognized, finding its way into fashion, advertising and even corporate logos, and yet the art itself is extremely controversial. It is subversive and self-affirmative, political, cutting-edge, and youth-oriented, with urban sensibilities. Yet the art is traditional, in that style and technique are passed on from master to pupil, and involve rigorous criticism from the community of artists within the discipline until the student has developed a distinct personal style of form and expressivity and has executed a masterpiece. Simultaneously performance art, process art, and public art, its imagery is inspired by mass culture, defined by bright bold colors, strong sweeping lines, and emphasis on three-dimensionality.

The word "graffiti" comes with a host of negative connotations. For many it is synonymous with urban degeneration and is a sign of gang presence, (According to the website, Art Crimes, this is the primary misconception expressed about graffiti. Graffiti artist Kairos is quoted as saying the gang-related graffiti accounts for only about ten percent of what you see, and it is considered to be done in "poorer taste" and lacking style. To look up other common misperceptions I recommend the article, "Everything you ever wanted to know about graffiti but couldn't find anyone to ask," at http://www.graffiti.org/faq/graffiti_questions.html.) a symbol of juvenile delinquency and crime-ridden streets. Yet whatever idea one may have about graffiti, judged from the above description, it can be defined as a form of artistic expression. Graffiti has been present in society since the advent of written language, found at archeological sites of ancient Egypt, Greece, and most notably, Pompeii. It is mentioned in the Bible as "the writing on the wall," (Daniel. 5: (New Living Translation) http://bibleresources.bible.com/index.php.) the message written by a mysterious hand foretelling the death of the king. Modern graffiti can be found on all variety of public surfaces, from bathroom walls to subway stations, but the graffiti that will be discussed here is defined by Nancy McDonald, in her 2001 book, The Graffiti Subculture as "street, 'hip-hop' or subcultural graffiti." (McDonald, Nancy, The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 2.)

the history of hip-hop and graffiti

This kind of graffiti was developed in the 1970's in New York, and is often referred to as a pillar of hip-hop culture, the visual art to complement the music and dance elements: DJing, MCing, and breakdancing. Hip-hop is a street culture born of the necessity to express oneself, even if one is too impoverished and marginalized to afford the conventional tools of art-instruments, paint, canvas, or education. For example, in hip-hop, a band needs very little equipment to make music, just a few records, turntables, and a microphone. Just the same, to create visual art in the hip-hop medium, the artist needs only the side of a train car and a marker or a few cans of stolen spraypaint.

The very illegality of graffiti informs its aesthetics, subject matter, and even motivation. Stealth and speed are of the essence. Spraypaint and paint markers became the medium of choice, as one can very quickly apply large amounts of paint before being caught by the police for defacement of property. (Sartwell, Crispin, "Graffiti is a Traditional Art," (2003) http://www.crispinsartwell.com/graff.html.) The paints should be conspicuous (as in strong, clear colors), quick and cheap, preferably "shopliftable." (Sartwell) The aesthetic quality of graffiti is then directly related to the materials used. The sweeping lines afforded by spraypaint and the scrawl of paint markers, these visual characteristics provide the formal elements of graffiti and a recognizable, stylized "look." The factor of time plays a role in the form of graffiti. Three distinct types of compositions evolved-the "tag," the "throw-up," and the "piece"-according to the amount of time spent on each work. Tags are the quickest and most spontaneous, often using paint markers and are created when the writer has very little time and is in an insecure or watched area. Throw-ups are made when a writer is in a more secure location but, like tags, require relatively little time to produce, usually consisting of two colors, one for the outline, and one for filling in. Pieces, short for "masterpieces," are the mural-like graffiti, which are much more involved, requiring a detailed outline, many hours to complete, and sometimes produced in collaboration with others.

Although some graffiti art includes pictures, its essential subject remains the same-the name. Every graffiti artist, or 'writer,' chooses a short pseudonym, or 'tag,' usually three to seven letters long. ("Graffiti Introduction," http://www.graffiti.org/ faq/graffiti_intro.html.) Writers often choose their names according to the shape of the letters and how adaptable they are to stylization and manipulation; an 'A' for example has many more graphic possibilities than an 'I.' From quick, spontaneous "tags," to large thought-out "pieces," the main subject is the name itself. For most graffiti artists, the compulsive writing of one's name over and over in public spaces is the primary impulse; therefore they call themselves "writers" rather than "painters." (Neelon, Caleb, "Critical Terms for Graffiti Study," (2003) http://www.graffiti.org/faq/critical_terms_sonik.html.) The more tags, or "ups," a person has written around the city, the more notoriety the writer will achieve, of course with style taken into consideration. For instance, if a writer has tagged everywhere but his tag lacks style, he gains no respect and is considered a "toy," or novice. The development of a personal and unique style is the young writer's first and foremost ambition. ("Graffiti Introduction")

The motivation of graffiti writers also has a strong connection to the illegality of the art. Many describe that the impetus for writing comes from the experience of the "rush" or "buzz" that accompanies this illicit act. There is an element of rebellion in graffiti-a protest through the defacement of property.

In her critical review of approaches to researching graffiti, Jane Gadsby outlines and translates the work of Regina Blume, from her studies on the motivation of graffiti writers, providing a helpful chart (Fig 1). Blume conducted her research in Germany, and found the shared motivation of graffiti writing is the aim of communication between the writer and the public at large or other individuals. (Gadsby, Jane M., "Looking at the Writing on the Wall: A Critical Review and Taxonomy of Graffiti Texts," (1995) http://www.graffiti.org/faq/critical.review.html.) Although the graffiti she studied was not exclusively the graffiti of the hip-hop subculture, her model still provides some insight. In hip-hop graffiti, the intended audience in many cases informs the style used. If the intended audience is the general public, writers may be inclined to make their statement more legible. If communicating to other graffiti writers is their aim, they might use the complicated and virtually illegible "wild style" graffiti, which can be read only by other writers.

Figure 1: Blume's motivational approach for studying graffiti as illustrated by Gadsby.

Blume's analysis focuses on the individual's motives for writing graffiti rather than the motives of a graffiti writing community or subculture. (Gadsby, Jane M., "Looking at the Writing on the Wall...") However, in subcultural graffiti much of the impetus to write derives from the values of the hip-hop community, stemming from a central message of hip-hop culture. As Ian Condry's research states, the message and common theme in the lyrics of the music, is that the "youth need to speak out for themselves." (Condry, Ian, "Japanese Hip-Hop and the Globalization of Popular Culture," in Urban Life: Readings in the Anthropology of the City, Eds. George Gmelch and Walter Zenner (Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press, 2001), 383.) In this light, one can view graffiti writing as a form of speaking out, of expressing oneself in a way that the whole world can, or must, see it.

At the time of graffiti art's inception, the economic and social context of recession, high unemployment, and racism of New York in the 1970's gave rise to an attitude of resentment from urban youth. Graffiti was an expression of this resentment, an act of protest against the mainstream, often referred to in terms of war. In fact the act of going out to write graffiti is known as "bombing." In the documentary "Style Wars," which explored the graffiti subculture of New York in the early days, the graffiti writers described their work as an effort to "bomb all lines," or to put their mark on every subway train in the city. So in a way, graffiti is an act of war-the kids against the system.

Given this context, then, I would like to explore the phenomenon of graffiti in one of the richest, most privileged countries in the world-Japan. How did this subversive inner-city culture spread to a country lacking those extreme divides of wealth, education and race that characterize a country like America and a city like New York? What do the kids of Japan have to complain about? Vanessa Altman Siegal, in her essay "Raw Like Sushi," proposes that Japanese youth believe that any popular culture from America is "cool" and therefore desirable. (Altman Siegal, Vanessa "Raw Like Sushi," (1996) http://eserver.org/zine375/issue1/living5.html.) One young Japanese person she interviewed, Keichiro Suzuki, clad in gear befitting an "LA gangsta," had this to say about hip-hop culture-"'I like Black people and their music because they're cool.'" Though she admits some hip-hop lyrics are socially conscious, Siegal argues that the Japanese are simply imitating the fashion and style of hip-hop and because of the language barrier they are missing the social issues at the root of the culture. Is this the case for Japanese graffiti? Is it merely imitation?

hip-hop in japan

According to Ian Condry, the leading scholar on the subject of Japanese hip-hop music, New York's burgeoning hip-hop scene made its first impact in Japan in 1983 with the opening of the film "Wild Style." The film debut featured rappers, dancers and graffiti artists, who came to Tokyo to perform and promote the film, influencing a future generation of Japanese DJs, breakdancers and graffiti writers. (Condry, Ian, "A History of Japanese Hip-Hop: Street Dance, Club Scene, Pop Market." In Global Noise: Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the USA. Ed. Tony Mitchell (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 228.) This was a seminal moment for many in this future generation, their first exposure to this vibrant culture. In an interview, DJ Krush, now a world-famous hip-hop DJ, remarked on his feelings at the time, "they [Wild Style] came to Japan and took over an entire floor in a department store. I was just amazed by them." (DJ Krush [interview by Spence D), The Bomb 43 (1995), http://www.geocities.com/krushter/interview-spence.htm.) He went out the next day and bought turntables and mixer and began scratching. In the years following the opening of "Wild Style," Tokyo's Yoyogi Park would see a gathering of Japanese youth on Sundays breakdancing and DJing-a tradition that continues to this day.

The first aspect of hip-hop culture that was widely appropriated by Japanese youth was breakdancing. (Interestingly, the developments of breakdancing moves in New York owe a debt to East Asia. One of the original "b-boys," or breakdancers, Crazy Legs, is quoted as saying, "The only place I'd say we learned moves from...was karate flicks on Forty-second Street, 'cause those movies are filmed the best, you could see the movement of the whole body (From Condry, 'A History')." Even today its influence on youth culture is undeniable: any excursion into the shopping centers after dark will result in an encounter with Japanese teens, cardboard spread on the ground in front of the mirror-like, darkened shop windows, practicing for the weekend's hip-hop nightclubs. Condry believes that the reason breakdancing experienced such an enthusiastic response is because its distinctive physical nature crossed linguistic and cultural barriers with relative ease. (Condry, "A History," 229.)

In contrast, because of linguistic differences, hip-hop music took longer to catch on. Young Japanese adherents could not understand the majority of the lyrics from American hip-hop songs, and instead analyzed and appreciated the rapper's rhythm, flow and voice. It took nearly a decade before Japanese rappers started to gain any notoriety, partly because of inherent differences between English and Japanese. Japanese is unaccented, and because the syllabic structure lends itself to few rhyming patterns as a result of the limited amount of endings at the conclusion of phrases. (For instance, contrasted with the incredible variety of English word endings, consisting of any combination of vowel sounds, diphthongs and consonants, a rap in Japanese would inevitably get boring because Japanese words end with only 6 possible pronunciations (-a, -i, -u, -e, -o, and n).) Japanese rappers referred to this linguistic dilemma as "the impossible wall," (Condry, "A History," 232.) but by the mid '90's had overcome it by introducing English phrases for the purpose of rhyme and simulating accentuation on certain Japanese syllables to give it "rhythmic punctuation." (Opsit.)

But even though the Japanese learned how to adjust their language to fit the style of rap, could they create hip-hop that was meaningful, real, or relevant? This question of what is "real" (riaru), and what is just imitation (mane) is fiercely debated among Japanese hip-hop fans. (Condry, Ian, "The Social Production of Difference: Imitation and Authenticity in Japanese Rap Music." In Transactions, Transgressions, and Transformations. Eds. Heide Fehrenbach and Uta G. Poiger (New York: Berghan Books, 2000), 166.) Ian Condry's essay, "The Social Production of Difference," addresses this debate, reminding us that it is dangerous to examine Japanese culture and its interaction with hip-hop culture, because one runs the risk of essentializing both, assuming universal characteristics that can be compared and contrasted, over-generalizing the complexities of cultural interaction. Instead, one should investigate how, like language and social processes, popular culture is involved in the "construction of identity." Popular culture can be a way of defining oneself in contrast to and in defiance of mainstream society, a kind of "generational protest." For instance, by appropriating English phrases and altering the way Japanese is pronounced in order to fit the hip hop medium Japanese youth created a "new dialect" (Fig 2), one that enabled them, through language, to "produce social difference," or distinguish themselves from the mainstream.

But is distinguishing oneself through the appropriation and imitation of another culture an acceptable way of constructing identity? One hears stories of the lengths Afro-phile Japanese youth go to, including expensive treatments of skin dying and dreading the hair. To many other hip-hoppers, these represent the superficial mane of the Japanese hip-hop scene, as one of the tenets of hip-hop is "keeping it real" and staying true to who you are. "'It is not the case that 'black' equals 'hip hop,'" says Zeebra, a Japanese MC who defends hip-hop as a globally inclusive cultural movement rather than a racially exclusive one, "'To fight the chaos together, and with all our hearts to spread hip-hop, I am certain that this is the greatest respect that can be paid to the originators.'" (Zeebra, Quoted from Condry, "The Social Production of Difference," 176.)

Dreadheaded and tanned Japanese youth walking around everywhere may contribute to the fear that hip-hop is resulting in a "loss of Japanese culture," but Condry urges us not to think in such simple terms. He argues that through a "process of localization" hip-hop takes on a new, uniquely Japanese meaning, "mediated through local language and key sites of performance." (Condry, "Japanese Hip-Hop," 372.) This process takes place at the genba, or "actual site," as in the local nightclubs where the hip-hop scene of Japan performs, socializes and networks. At the genba, hip-hop music expressed in their own language and addressing their own issues, takes on a Japanese context, setting it apart from, but not completely denying its New York City street culture roots. Just because Japanese youth are enamored of American hip-hop and rap music, it doesn't signal a complete osmosis of American hip-hop values or ghetto context. In fact, Japanese hip-hop lyrics contain practically no references to hard drugs, guns, or misogynous behavior. (Condry, "A History," 223.) Not surprisingly, the rise of hip-hop music also hasn't meant a rise in gangs or violent crime in Japan.

But it has meant a rise in the crime of vandalism-namely graffiti. (Japan has a native word for graffiti, "rakugaki", but this term usually describes simple etchings of the "yoko likes yuya" or "ichiro is a geek" variety.) Condry mentions that, in the early 90's, graffiti was the last aspect of hip-hop culture to break through in Japan. (Condry, "A History," 227.) Graffiti writing in Japan could be considered just coming out of its infant stages-yet has proved to have a style quite its own. This style is so compelling that in 2005 a major contemporary art museum decided to create an exhibit entirely devoted to showcasing Japanese graffiti writers. The "X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan" exhibit at the Art Tower Mito, as curator Kenji Kubota says, is the first of its kind-inviting writers from all over Japan to tag up the museum walls and create pieces throughout the city, inviting the viewer to consider "the potential and fascination of graffiti as art." (Kubota Kenji, "Beautiful Deviation," in X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan (Tokyo: Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, 2005).)

the ramm:ell:zee vs. samo aka jean-michel basquiat

THIS IS TO DISPROVE THE OLD MOTHER'S TALE THAT WORDS WILL OR CAN NEVER HURT YOU! IKONOKLAST PANZERISM introduced by so-called graffiti for the remanipulation by and from energy through the body for the repercussions and rediscussions of society's misleading reductional break-down.

RAMM:ELL:ZEE, the, "Ionic Treatise Gothic Futurism Assassin Knowledges of the Remanipulated Square Point's: One to 720° to 1440°." (1979, revised 2003) http://www.gothicfuturism.com/rammellzee/01.html.)

On the television screen a man in an elaborate mask, a futuristic neon-painted samurai-inspired helmet, rants and raves, nearly unintelligibly. Though the camera angle is close, behind him you can see his artwork: trash sculptures of brightly colored baubles, children's toys, discarded electronic equipment, garish fabrics, rockets, arrows, toy guns; carefully, obsessively arranged, and so densely packed that details are hardly discernible, a compulsive collection of clutter. He speaks in convoluted sentences, sometimes laughing, sometimes raising his voice, and using words with a meaning known only to him. In any other context you might walk right past him, ignore him, dismiss him as some schizophrenic black man ranting at the world on a street corner. But this is the RAMM:ELL:ZEE, one of the originators of hip-hop culture: MC, graffiti artist and philosopher.

As you enter the "X-COLOR/Graffiti in Japan" exhibit at the Art Tower Mito, the first room is dedicated to the RAMM:ELL:ZEE and his theories on graffiti art and culture. The interview on the television is accompanied by sketches of armored letters. According to his philosophy of "Ikonoklast Panzerism," which he developed in 1979, graffiti is a weapon in a "Symbolic War," the battlefield being the sides of subway trains traveling like veins through the boroughs, "the (BLOOD SYSTEM) of New York City, (Universal Transit System) [sic]," (RAMM:ELL:ZEE, the, "Ionic Treatise) therefore the letters of graffiti must be armed with arrows, rocket launchers, harpoons-breaking out of their recognizable forms and becoming new symbols with great power

Figure 3: The RAMM:ELL:ZEE's visual breakdown of the structure of the Roman letter A. In his theory of 'Ikonoklast Panzerism,' he describes the qualities of and calculates equations for each letter with a pseudoscientific approach involving what he calls the 'sirpiereule,' an esoteric concept involving somehow the earth's electromagnetic field, quantum mechanics, and apocalyptic war.

The RAMM:ELL:ZEE developed a complicated and subversive philosophy against the government and educational system, and its institutionalized othering of class and race, tracing the origins of the conflict to the very building blocks of language-the letters. (RAMM:ELL:ZEE, the, "Ionic Treatise) Although it is nearly impossible to read and understand the theories that the

RAMM:ELL:ZEE writes in his manifesto due to the heavy use of mathematical equations, inventive grammatical structure, unusual jargon, and complex original mythologies involving a cast of futuristic warrior characters; it is clear that he is preparing for war. This is a cultural war, a race war, originating from the time the Romans, via the Greeks, appropriated and transformed Phoenician symbols into the Latin alphabet, setting in motion a system of oppression of African peoples through language and symbols, culminating in the educational divide that America exhibits today. The RAMM:ELL:ZEE's indecipherable style of writing may be a mockery of the language of academia, (Thiel, Axel. "Rammellzee's Message," (1997, 1999) http://users.aol.com/axelthielks/ram.html) which by its very nature is exclusionary against those without access to education. (This academic language became even more convoluted, daunting, and perhaps even insulting with the advent of postmodernism, which utilized an even more complex vocabulary of terms all the while discussing theories of cultural oppression. Take, for example, reading Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's article 'Can the Subaltern Speak?' to an Indian woman from a poor village. Though the content of the article concerns her directly, without the appropriate college degree it would make no sense.) So the RAMM:ELL:ZEE launched his own war of words, creating a cryptic treatise on the evolution of oppression through symbols and preparing his letters for battle on the subway lines of New York City (Figures 3, 4). Just as a monk decorated the letters of his manuscript with arabesques, the RAMM:ELL:ZEE decorates them with weaponry, arrows and rocket launchers. Graffiti writing on trains, or "bombing," is to him the evolution of a centuries-long protest of symbols, attacking the infrastructure of oppression. Writing becomes a pathogen, poisoning the "blood system" of the city. The more unintelligible the letters, the more impervious they are to attack or appropriation. Try as they might, the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority could not wash them away completely.

Figure 4: The full evolution of the armed letter according to the RAMM:ELL:ZEE.

Graffiti art has always had an uneasy relationship with the gallery systems of the fine art world, not to mention with society. Only a few graffiti artists have become successful by the standards of the contemporary art world, the most famous being Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. Interestingly, the museum's introduction to the history of graffiti did not involve these famous cross-over artists but presented the art of the elusive RAMM:ELL:ZEE. Though their iconography and methods had roots in graffiti and street art (Basquiat, with his SAMO tag, and Haring, with his chalked subway stick figures), they abandoned the street and the subway for canvases once they became darlings of the art world and started making money in the lucrative art market of the 80's. The RAMM:ELL:ZEE on the other hand has lived in relative obscurity, with minimal art media coverage. (Morris, David. "Biconicals of the Rammellzee," Pop Matters, May 13, 2004, http://www.popmatters.com/music/reviews/r/rammellzee-biconicals.shtml)

The choice to present his work as a preface to the exhibit made it clear that the X-COLOR would be an exploration into the underground world of graffiti, not an exportation of graffiti design into the setting of a gallery. Though written on the walls of a museum, the world of graffiti was presented within a cultural and socioeconomic framework, tracing its connections not only with art history, but also with the music and the subcultures of hip-hop and skateboarding.

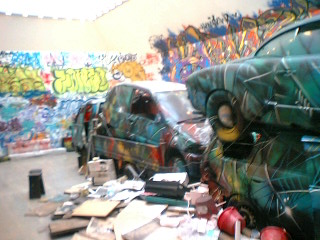

x-color --graffiti in japan / Graffiti in the gallery

Upon entering the exhibit, you enter the world of the graffiti artist, the back alley, the junkyard. In the center of the room there are junk cars stacked one on top of the other, tagged up completely (Figure 7). The walls of the museum are covered to the ceiling in tags (Figure 6); the floors are covered in debris, cardboard, car tires, discarded furniture. An old boombox hanging out of the window of one of the cars plays a tape of loud hip-hop. The only detail that belies the true location is the immaculate museum lighting, and the white, white floors.

This room is a recreation of an urban wasteland, the abandoned lots that serve as prime locations for graffiti. In her honors thesis for the University of Sydney, Ilse Scheepers asserts that graffiti "defines and is defined by urban space." (Scheepers, Ilse, "Graffiti and Urban Space," (2004) http://www.graffiti.org/faq/scheepers_graf_urban_space.html.) She argues that more than any other factor (such as class or race) it is the actual urban environment that causes graffiti. She feels that the sense of anonymity fostered by, and the animosity generated toward the concrete sprawl of the city landscape, motivates the writer to make a name for himself. In very much the same way a skateboarder engages his urban environment, the graffiti artist attacks concrete walls, and the city, in turn, is transformed into a landscape of self-assertion. One only has to look at the environment of urban and suburban Tokyo to see how this urge to differentiate oneself from the crowd can manifest itself in the city's young people, whether in outrageous fashion statements, rebellious music or graffiti. The graffiti writer Dopesac has described Tokyo as "one big ghetto," referring to his desire to rebel against the seemingly homogenous society steeped in strict social convention. (Okazaki Manami, "Tagging in Mito Galleries," Japan Times, 20 October, 2005, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/getarticle.pl5?fa20051020a1.htm.) Through graffiti, he can express his dissatisfaction with his environment, and at the same time assert himself as an individual.

The graffiti tag, besides being a form of self-assertion, is an exploration of style, a fragmentation and distortion of letters. Iseo Nose, the cooperative planner of the exhibit, describes it as "the modern day revival of hieroglyphs. " (Nose Iseo, "Graffiti-A Social Sculpture," in X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan (Tokyo: Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, 2005).) In his essay, "Graffiti-A Social Sculpture," he asserts that graffiti writing, exemplified by the RAMM:ELL:ZEE's alphabet, is "the most extreme form of Mannerism," in its over-stylized, exaggerated distortion of letters. Nose outlines the development of the "disguised letters" of graffiti as an extension of the hieroglyphic origins of the alphabet, the illuminated manuscripts, and the ideograms of archaic Chinese characters, in that the words take on an extra "mystic" dimension, unintelligible for those the script is not intended. (Nose Iseo) Therefore, the illegibility of Wild Style writing is not only a way to disguise a writer's identity; it contextualizes the name in a kind of shroud of mystery, like cryptic hieroglyphics.

In his essay, "Graffiti and Language," author and philosopher Crispin Sartwell traces the same path of the semiotics of graffiti script as a "history of unintelligibility," from the mystic traditions of the scribe, and the "magical significance" of ancient texts. (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language," 12 March, 2004, http://www.crispinsartwell.com/grafflang.htm.) He argues that before the advent of the printing press and the ideals that came with the Reformation, the laboriously copied and hand-embellished texts had an aura of mystery "in a world of illiterates." (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language") Just as the only people who can decode stylized graffiti and understand the slang-ridden vernacular of Japanese rap are members of the scene, these texts were reproduced for a minority of educated elites; "the idea was to mark off those who could read the lettering as a special group with its own language." (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language") This is strikingly similar to the RAMM:ELL:ZEE's philosophy of Ikonoklastic Panzerism, whereby the spoken word through the use of slang, and the written word through the manipulation of letters, obfuscates meaning in the face of the ruling oppressor-in his case, white, educated America. (Dery, Mark, "Black to the Future: Afrofuturism," In The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink, New York: Grove Press, 1999.)

An illegible message is frustrating, threatening and frightening and the one who can decipher it holds a position of power. In the Bible, even, a ghostly, anonymous hand that writes a message in a language he cannot read visits the king Belshazzar, of Babylon. Terrified, the king calls for Daniel to read the "writing on the wall," promising him riches and power. Daniel reads him the message; it is a prophecy of the judgment and fall of Babylon. Daniel receives his riches, but that night, the king is found dead. (Daniel. 5:1-31.) As Foucault and Deleuze have theorized, the written word is an instrument of power, the foundation upon which governments, kingdoms and dictatorships are built. (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language.") The written word that those in authority cannot read, then, undermines their power. In effect, the RAMM:ELL:ZEE's armored letters and wild style graffiti are the texts pronouncing the fall of the modern Babylon.

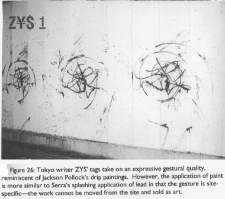

In the first room of the "X-COLOR" exhibit, this indecipherable type of lettering affronts you, transgressing the boundaries of the language with words distorted beyond recognition. Particularly complex are the letter styles of the writer DASTE; with layer upon layer of interlocking figures, there is no hope for decoding this monster. Indeed his tag literally takes on the form of a monster, replete with menacing eye and a jagged row of teeth (Figures 5, 6). In this way, his piece takes on a meaning that is, as Sartwell observes, "essentially pictorial rather than linguistic." (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language.") The text of the name, then, is transformed through the highly stylized manipulation of the individual letters to become a visual, symbolic representation of self.

The graffiti of KAMI and SASU complete this transformation by discarding the tag in favor of symbolic, personal iconographies. In fact, these two artists consider themselves painters rather than graffiti writers, bridging the line between subcultural graffiti and street art. (Kubota Kenji [Interview by Uleshka Asher), PingMag, 17 October, 2005, http://www.pingmag.jp/archives/2005/10/x_color_graffit_1.php.) Upon entering their space you are snapped back into the world of the contemporary art museum (Figure 8). A spacious area that features the wide, sharp-edged, signature line of KAMI curves around the entire room. This piece makes full use of the space and is free of the clutter of tagging. It is as if the line is a single, blown-up stroke of a spray can. SASU, one of only two women in the exhibit, is known for her self-pronounced "feminine" (SASU, Artist's statement, X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan.) approach to graffiti art, incorporating imagery of Buddhist and Hindu deities and mandala-like patterns. In the place of tags, this pair employs personal icons: SASU, a Kewpie-like face resembling the shape of a jingle bell (Figure 9), and KAMI, a squat vessel-shaped object (Figure 10).

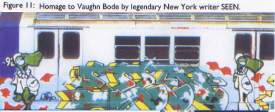

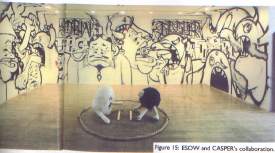

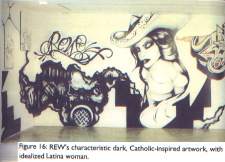

If icons serve as simple abstract symbols for the artist, and tags as pictorial, symbolic representations of self-reference, then images are the self-portraits of the artist. Use of images can help us understand more about the social and cultural construction of identity, through what the artist chooses to portray and how. Graffiti artists often draw their imagery from pop culture, especially from cartoons. Since the very early days of graffiti art, Vaughn Bode's bold, colorful drawings featuring big-breasted women, lizards and wizards were very popular. Angela Frucci, in her article on the legacy of Bode, describes the phenomenon of "a rite of passage," where graffiti artists incorporate his characters into their pieces (Figure 11), "making [him] an unwitting guru of urban street culture." (Frucci, Angela, "Following a Wiz to a Far-Out Oz," New York Times, 31 May, 2004, http://www.markbode.com/site/article_1.html.) Bode, who died at the age of 33 in 1975, never saw the widespread appropriation of his work, but writers today continue to pay homage to his imagery. In Japan, a country with a rich heritage of graphic arts, anime- and video game-inspired characters are commonly found in graffiti. Many Japanese writers create their own repertoire of characters (Figures 12-14) that reveal content and narrative in their work. One of the more amusing examples of this at the "X-COLOR" exhibit was the collaboration between CASPER and ESOW (Figure 15). The scene is black and white, with only touches of red paint as blood, depicting the struggle between some helpless looking men and some very bossy, horned, pickle-shaped monsters with enormous mouths. This narrative is continued with the sculpture in the middle of the room, where the pickle monster faces off against a black furball of a man in a sumo ring, complete with sand. Exactly what struggle is referenced in that piece is beyond my powers of deduction, but what I believe is truly communicated is a strong conveyance of Japanese identity. This national identification is visible in many of the characters created by Japanese graffiti writers. In contrast, the work of REW, shows a strong Latin-American influence (Figure 16), revealing his cultural heritage as an ethnic Japanese from South America. (REW, Artist's statement, X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan.) The development of the use of imagery in the paradigm of Japanese popular culture and personal iconography is a convincing indicator that graffiti in Japan has progressed past any purely imitative (mane) stage.

One Japanese artist stands out as one of the most distinctive graffiti artists worldwide, with an instantly recognizable iconography, and a most unique style: the Tokyo-based QP. In simple black and white, the letters Q and P are juxtaposed and abstracted, the form suggesting a Kanji ideogram (Figures 17-20). In QP's installation at the "X-COLOR" exhibit, no inch of surface was left uncovered, from paint drips and footprints across the floor, to tags lining the inside of a refrigerator and microwave, highlighting the prolific nature of his work and the ubiquity of graffiti in general. QP's street pieces are often found in out of the ordinary but easily overlooked spots. Sometimes in series, emphasizing the patterns of the urban landscape, enumerating such things as the landings of a stairwell or the floors of an apartment building. This approach brings to our attention those spaces that would ordinarily escape unnoticed, by revealing to us, through graffiti, codes and patterns in our environment.

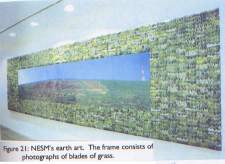

One of the most unique approaches to the environment is found in the work of the writer NESM, who, using garden tools cut enormous letters into the hillside, so big that they could be seen from an airplane (Figures 21). (Kubota Kenji [Interview by Uleshka Asher].) When I encountered his work, it struck me as the graffiti equivalent of Ana Mendieta's photographs of the imprints her body made in tall grasses. Mendieta used her own body to make her mark but in graffiti, the name serves as a representation the body and self. When the writer leaves his tag it is a record of where he or she has physically been, the body's movements through space. In this instance, NESM took graffiti art and stretched its boundaries, out of the city, using unusual materials.

For some artists, the interaction with space as a record of travel takes precedent over the visual, pictorial endeavor. Perhaps the most prolific artists represented at the "X-COLOR" exhibit is the self-described "all-city king" ( According to the Art Crimes website's graffiti glossary, all-city is "What a writer is considered to be when he/she is 'up' [whose work appears regularly everywhere], but this term implies more status than being just 'up.' Many people can be 'up,' but only a select few could be considered 'all city.'" http://www.graffiti.org/faq/graffiti.glossary.html.) VERY (Figures 22, 23). Out of all the graffiti artists in Japan, I believe I came across his work most frequently while out in the streets. Perusing his webpage, you can see walls from San Francisco to Seoul and everywhere in between. His section of the exhibit consisted only of a few playful throw-ups, accompanied by an impressive number of photographs documenting his travels throughout Asia and America, accentuating the profusion and abundance of his work rather than any particular masterpiece.

VERY engages space by laying claim to every corner of the world, NESM by cutting his name into the earth, and QP by bringing attention to unnoticed spaces and patterns in our surroundings. Though they are different approaches, they work in essentially the same way, in that they transform the environment through the inscription of text. Kubota feels that this transformation offers opportunities to "re-read" Kubota Kenji [Interview by Ozaki Tetsuya], ARTiT, vol. 3, no. 4, Fall/Winter 2005.) our urban environs, to have an unexpected visual encounter with the concrete walls of parking lots and the sides of trains, and to experience a new take on what was at best banal and uninteresting, at worst oppressive and depressing.

graffiti and mass marketing

In recent times, these urban spaces have become a battlefield. Many have commented that graffiti serves as an alternative to mass advertising. Perpetrated in anonymity, with stolen spraypaint, graffiti writers create public signs and symbols outside of the structure of capitalism. As Japanese rapper ECD maintains, the primary objection to graffiti is that it "renders things un-salable" by covering surfaces that could have been potential advertising spaces, such as the sides of subway trains, walls, and billboards. Recently, however, the corporation has found a way to subvert this situation by appropriating the actual medium of graffiti in order to market to "urban nomads," as Sony's spokesperson, Molly Smith called their target consumer. (Smith, Molly, Quoted in Singel, Ryan, "Sony Draws Ire with PSP Graffiti," Wired News, 5 December, 2005, http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,69741,00.html?tw=wn_2culthead.) In 2005 Sony hired artists in several American cities to apply, as graffiti, an advertisement styled after the graffiti aesthetic, featuring the image of kids playing with what looks like a PlayStation Portable product. The images omit any textual mention of brand name. This campaign has been greeted with a backlash, especially on the streets of San Francisco, where a counter-attack is taking the form of red spraypaint over the images and a mockery of their logo as "Fony," among other biting commentaries (Figure 24). Sony defends itself, however, as they had purchased the right to apply the graffiti on private property directly from the building owners. Apparently Sony convinced them that an adequate price for two weeks advertising time was a shocking hundred dollars. (Smith, Molly)

Figure 24: The hip-hop graffiti styled character pandering to the "urban" crowd is countered by a very clearly written refusal to accept such appropriation.

Perhaps this is a signal for the coming symbolic and cultural war the RAMM:ELL:ZEE prophesied. If the icons and images and now actual spaces and methods of graffiti can be appropriated by mass marketing, the only way to protect against the appropriation of graffiti texts is by obscuring, fragmenting, and distorting them, rendering them illegible and therefore incapable of conveying the information required to advertise products. (Sartwell, "Graffiti and Language.") Graffiti is a method to subvert the institutions that rely on the power of the written word-government, advertising media, and education. The RAMM:ELL:ZEE believed that education was essentially the establishment of oppression through language and symbols. In the education system of Japan the study of reading and writing is rigorous and severe, and through symbols and language the acquisition of social codes is imposed by rote, all the while discouraging individual expression. The education system is highly standardized, inevitably othering the student. Othering, as Terry McVannel Erwin defines it, "essentializes by portraying dominant cultural ideologies as the one, true, legitimate knowledge," (McVannel Erwin, Terry, "Addressing the Issue of Othering in Counselor-Education Programs," http://www.ohiocounselingassoc.com/docs/Othering-Final%20Revision%20.doc.) thereby encouraging conformity and marginalizing students who don't fit in the common paradigm. In Japan it seems this conformity is further enforced by the policy of school uniforms and the nature of rote learning, the effect of which can be likened to a practical "same-ing" of students.

MC Shiro of Rhymester calls hip-hop, in defiance of mainstream Japanese society, a "culture of the first person singular," (MC Shiro, Quoted in Condry, "Japanese Hip-Hop," 383.) a self-aware and self-affirmative movement. But since its inception in New York, hip-hop values have experienced a shift. Where hip-hop originated out of necessity for self-expression despite scarcity of resources, as a counter-culture in an environment of urban decay, now hip-hop is global pop culture, and on the surface very oriented towards the display of wealth. Although the popularity of hip-hop music and style is often harnessed by corporations to peddle their products to young people, Ian Condry shows us that in Japan the essential "speak up, speak out" message of hip-hop, presented to a culture devoted to group harmony, is "in some limited sense, revolutionary." (Condry, "Japanese Hip-Hop," 384.) This basic sense self-awareness equips young people with a means to "imagine" their own identity, and a means of differentiating themselves from a homogenous society. (Opsit.)

Japanese graffiti writer SUIKO describes his motive for writing graffiti as "a way of rebelling against the faceless order of modern society." (SUIKO, "X-COLOR Graffiti in Japan," ARTiT, vol. 3, no. 4, Fall/Winter 2005.) The social climate of Japan-where group harmony is emphasized over individual rights, where security cameras subject each person to the magnitude that Kubota calls it "obsessive monitoring," (Kubota Kenji, "Beautiful Deviation.") where the education system produces kids who can pass a test but can't think for themselves, and where mass marketing inundates every facet of daily life-provides a compelling environment for graffiti to appear. Kubota considers it a breath of "fresh air...trying to win back the freedom and creativity being suppressed in modern society." (Kubota Kenji) The signs and symbols that appear uninvited in urban spaces are testament to an underground community persistently protesting the status quo.

Graffiti exists as a "social sculpture" (Nose Iseo, "Graffiti-A Social Sculpture.") outside of the mechanisms of capitalism and is a force that a gallery cannot completely capture. It does not necessarily belong in the world of contemporary art, each piece tied inextricably to a certain place and time and to a distinct community of artists operating outside of the capital-driven art market. Richard Serra, in 1969, first questioned the relationship between art, ownership, and site-specificity with his "Splashing" of molten lead along a gallery wall (Figure 25), a work of art that could never be sold. So too with graffiti, as it exists on the street it is independent (Figure 26): outside of the world of art, outside of the concept of ownership, and to a degree outside of the ever further commodified hip-hop culture. Graffiti requires no investment; it generates no income, therefore it is of no interest to corporations (except now as a despicable marketing strategy or appropriation of style), unlike the highly profitable hip-hop music business. It exists for its own sake, an impulse of the most primitive order, stylized to the highest degree, a reaction to and a transformation of the urban environment. Its only use to the observer is as a means to a new perspective, and Kubota hopes that visitors of the exhibit, by understanding that, "can enjoy life more when walking in the streets." (Kubota Kenji [Interview by Uleshka Asher].)

Japan's urban youth, though they don't necessarily suffer from the same social divides as in New York; nevertheless suffer from the alienation afforded by the sprawl of urban landscape, hyper-consumerism, the pressures of the school system, and the othering of cultural homogeneity. Graffiti is a means of protest and of asserting one's individuality; as the writer KRESS says, "graffiti is communication." (KRESS, "Possibilities of Street Expression" (symposium, Yokohama 2005: International Triennale of Contemporary Art, Yokohama, October 29, 2005).) Whether communicating to other writers your prowess in wild style, or making a statement of protest, graffiti questions, informs, and transforms space, giving expression to the blank, concrete walls of the city.

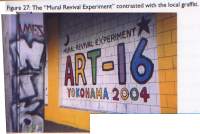

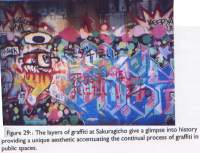

Along the concrete supports for the train tracks at Sakuragicho station in Yokohama, there is an ever-changing gallery of graffiti art that extends for hundreds of meters. This has been a safe spot for bombing for over a decade, and the pieces reflect that: elaborate, layered one upon the other, dating back to the beginnings of graffiti art in Japan. Without the graffiti, this wall would be drab and of no interest to anyone, but through the actions of the writers it has become an area of cultural interest. In 2004 the Yokohama art group, Art 16, tried something called a "Mural Revival Experiment," covering over some of the panels of graffiti with murals (Figure 27). Some of these were more successful than others in conveying the qualities of street art. For the most part, however, even the less successful ones were left intact and only a few were rejected and tagged over (Figure 28). Sakuragicho exemplifies the relationship between graffiti and the art world-they can generally live side by side, but the art world continually invites its own erasure by trying to "revive" the streets, failing to see the beauty of the raw expressivity of graffiti. Operating outside of the gallery and grant system, there is no curatorial staff or grant board separating the viewer from the experience and pure encounter with graffiti art. Its mystic hieroglyphics, then, engage the environment with an immediacy and authenticity like no other form of public art.

From the walls of Sakuragicho to the walls inside the Art Tower Mito, graffiti in Japan is replete with visionaries, unique styles, and talent. Graffiti has come a long way from its New York City roots, spread throughout the world, and taken on new contexts and styles with each individual who picks up a spray can. In Japan, a country of strict social codes, it has provided an outlet and an identity for creative young people, a way for them to claim their environment. They challenge the viewer to recognize the semiotics that define their surroundings, from the municipal text of street signs and the suggestive symbols of advertising, to the scripts of graffiti-illegal, illegible, and iconic. Graffiti writers present the landscape and infrastructure of the city as a document with the hidden codes revealed. It is a narrative of the city, the inscription of its conflicts and triumphs, and the transformation of its infrastructure from one of grey concrete to wild, vivid colors.

fig. 1

fig. 2

fig. 2

fig. 3

fig. 4

fig. 5

fig. 6

fig. 7

fig. 8

fig. 9

fig. 10

fig. 11

fig. 12

fig. 13

fig. 14

fig. 15

fig. 16

fig. 17

fig. 18

fig. 19

fig. 20

fig. 21

fig. 22

fig. 23

fig 24

fig. 25

fig. 26

fig. 27

fig. 28

fig. 29

cars by Kane

cars by Kane

Kami & Sasu

Kami & Sasu

Kami & Sasu

Huze

Huze?

Very

Zone

Zone

Zone

Zone

QP

QP

Sklawl

Suiko

Kress

QP

Kami & Sasu

Kami & Sasu

Esow & Casper